Eric Harper and Matt Lee, part of The Freudian Spaceship research project, draft text for the online thesaurus of concepts, September 2023

Question: In the Breath text, you state that the contemporary age is not one of anxiety so much as it is one of forgetting and autism. How do you understand anxiety in this scenario?

Within the West, different generations get labelled. This is a peculiar process, unofficial but traditional, and a very twentieth century phenomena. There are currently seven generations: the Greatest Generation (1901-1924), the Silent Generation (1925-1945), Baby Boomers (1946-1964), Generation X (1965-1980), Millennials (1981-1996), Generation Z (1997-2012) and Generation Alpha (2013-2025).

What is peculiar about this ordering of people into generations is that it is a recognition of a differentiation process that happens to children, distinguishing between one group and another because of the way they were brought up. That is, it recognises a historical sociogenic structure. It recognises the enormous impact of cultural and social structures on the human, specifically on the human child but also on the minds of that generation. It is as though each generation were a slightly distinct species, with a different shared cultural space and, so, a different ability to understand the world around them. There are, it is said, generational differences and this refers not to a biological or physiological difference but to a different mindset. This can become a political feature as a new generation comes into political agency. In the UK, for instance, there have been attempts to connect the Corbyn moment to this generational structuring process.

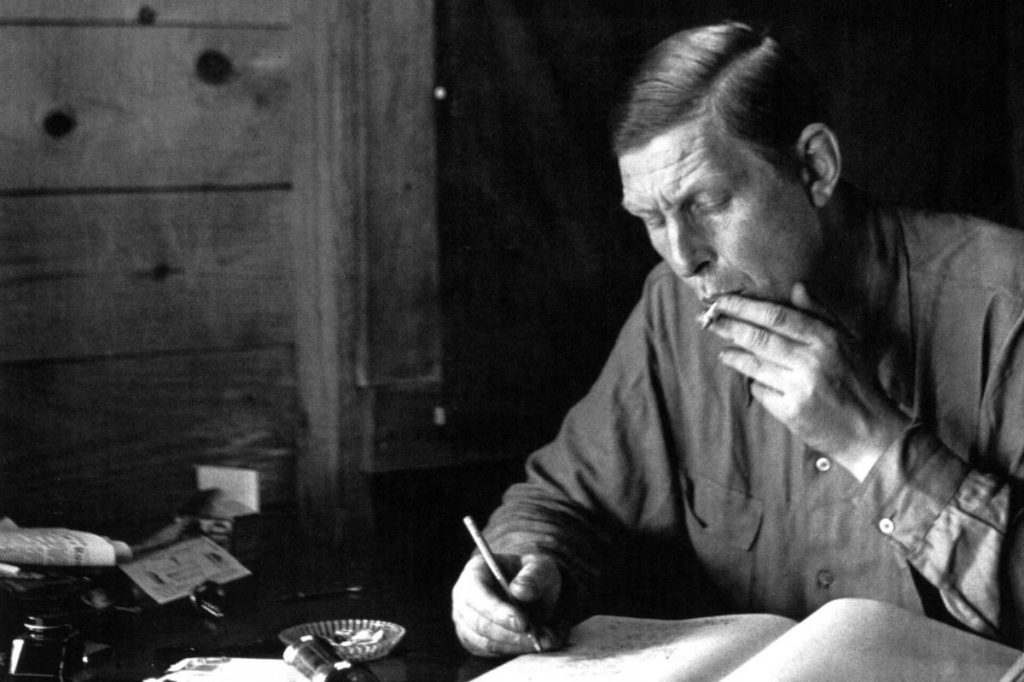

Baby boomers are thought of – perhaps only by themselves – as self-sufficient, competitive, and committed, but they were shadowed by another label, the age of anxiety. This was inspired by the W H Auden poem of 1947 called The Age of Anxiety. Auden’s poem, set within a cultural space in New York at the end of the Second World War, picks up the shattering of a world and the peculiar loss of connection that occurs with the persistence of war, violence, and terror. The background of destruction in the news that cannot be ignored and yet must be ignored produces a curious withdrawal and shift into a sensation of disconnection.

The age of anxiety is a poor image in many ways. It can too easily suggest a heightened heart rate, a rapid breath, a trembling and shaking body. Whilst this image of a moment of anxiety might come to mind, an age of anxiety produces instead a kind of flatness, a dissociated body, a disconnection as the persistent anxiety of war, violence and terror gradually becomes the normal state of the body. A moment is different from an age. The age of anxiety refers not to the moment of anxiousness but to the normalisation of persistent fear, to the shift that occurs as the body adapts and forgets anything other than this continuous, ongoing threat, to the point of forgetting what it feels like to be threatened. This is the purpose of adaptation, to enable the body to continue despite something hostile to the body. There is no adaptation needed without a threat to the body. What must be remembered, however, is the temporality of the threat – temporary or persistent? Momentary or continuous?

When feeling overwhelmed we want to reduce the scale of something, thereby making it less overwhelming. Fear often shrinks a person’s ability to reach out to others and speak back. We see this with human rights violations, with people feeling isolation and shame. The sense of isolation and shame is something perpetrators can trade on, aware that the humiliation, degradation, and threat of further pain often works to shut people up, making them unable to expose what has happened. It is a process that can disconnect us from the flowers that greet us outside our front door and the truth that lives in our bodies.

On an everyday level we see this fear operate in workspaces in those moments of the threat of punishment and burn out. To be the one who is blamed is to become some object in another’s world, to be positioned negatively and often disempowered. In these moments, internal and external fear converge, thereby magnifying the fear. Openness is replaced by shutting down, disappearing and defensive actions to stop the feeling of annihilation. This is a core element of anxiety.

The result of this response to the feeling of annihilation, to talk in psychoanalytic terms for a moment, is an arrest of vitality and positive development, a withdrawal of libido from objects and people in the external world (Abraham and Freud). Instead of investments in life, in growth and a future – a libidinal cathexis of the object – there is a libidinal cathexis of the ego through withdrawal of the libido from the external world onto the ego. Central to this process is a dynamic of increasingly living within a phantasy, up to and beyond the point at which the phantasy begins to actively conflict with the external world, producing a situation in which things no longer fit together well enough to enable growth.

The process of phantasy, the process of connecting to the world through an internal image that projects onto the world rather than which simply arises as a kind of reflection of the world internally, is normal and necessary for any mind. This, at least, is a key moment in psychoanalytic theory. Distinct from the conscious images of a fantasy life, the phantasy works unconsciously, by satisfying instinctual drives, through processes of adaptation. Just like the unconscious itself, it cannot be shown directly but is available only through inference, through the idea of a process that operates with its own dynamics, dynamics that are not themselves organised by us but rather which organise us, produce us. Despite the many ways in which such processes might be theoretically stated, the core idea is that of a productive process, out of which the mind and the self emerge, and which has its own dynamics that can be distinct from and even at odds with our conscious desires or intentions.

Anxiety occurs when we become aware that we are no longer plugged into the world in the way we were previously, it is a disruption of the way we connected and linked things together, including our own selves. An object or idea that was safe suddenly becomes threatening. Something that previously did not exist in our minds suddenly comes to dominate our every thought. The links we had come under attack and break. For Wilfrid Bion, an attack on links can produce a situation in which we are all at sea, without a haven (Bowlby). Vulnerability, helplessness, and an inability to mask over this insecurity can produce an imminent threat of non-being in which we are unable to imagine an existence beyond our earlier attachments and we experience a closing down of the new and the unknown as we struggle to keep any sense of safety amidst the chaotic disruption. Anxiety can be a site of restlessness, subject to intolerable and unbearable sensations. Anxiety in this formulation is the spider web of repetitive thought, to be stuck within a web of implications or a whirlwind of possibilities, a tornado of thoughts. Freud spoke of that which was both intolerable and incompatible.

Within Freud’s 1926 essay Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety the emphasis shifts from what we might call ‘the outside’ towards a more ‘internal’ dynamic. Emphasis is placed on an expected loss that results in what he calls ‘signal anxiety’. Signal anxiety is about an expected event, not an actual moment of threat, and as such arises in a complex process, entangled as it is in the phantasy life of the mind. What we feel as a threat is not simply an external object in relation to us, rather what feels threatening can now arise anywhere and anytime, a constant haunting presence of a future catastrophe.

Freud renovates his earlier theories in this 1926 work, no longer thinking of anxiety as arising from repression but inverting the relationship such that anxiety now causes repression. The ego is called on to respond to the demands of the superego and produce a substitute for a basic drive satisfaction that will lead to repression in the form of an inhibition which aims to avoid further repression. However, the superego is never satisfied and demands the impossible, producing a situation of having to live up to an internalised ideal, resulting, in the worst-case scenarios, in negatively experienced symptoms and a reduction to an abject and unlovable state. Anxiety is no longer seen as a reaction to the loss of the object of satisfaction and benevolent care, as in the separation from the mother for example, or the actual loss of the object, which is mourning. Now anxiety comes about due to fear of the loss of a sense of self. In this situation the superego can reduce the person to an abject and unlovable state, as with shame. The person can feel excommunicated from the human, from any identity, placed into a position that is ‘unlovable’ and even into a kind of ‘social death’.

For Anna Freud, the ego is both subject to anxiety and an agent of anxiety. Anna Freud is interested in the ego, in the way it functions and the way it copes with anxiety, in those defences used by the ego to reduce conflict between the id and superego. The failed attempt to find a substitute satisfaction results in a symptom, in defence and anxiety. Reality, id, and superego make conflicting demands upon the ego resulting in distinct kinds of anxiety. For Anna Freud, anxiety caused by the forces of the instinctual id result in neurotic anxiety and ego conflict, whilst anxiety caused by the superego results in moral anxiety and guilt feelings and anxiety caused by reality, the material reality of the situation, produces frustration.

Melanie Klein wants us to pay attention to the place of greatest intensity within the experience. Intensity cannot be reduced to anxiety, but anxiety is an expression of one kind of intensity, which we need to understand and engage. For Melanie Klein, for example, the focus of the analytic session should be on the point of greatest anxiety, which she links to a sense of urgency, immediacy. It consumes the person and due to being overwhelmed with anxiety, as one’s very sense of being in the world, our life relationships are under threat, we struggle or simply cannot take things in. If anything is taken in, it is often experienced as persecutory and bad. Instead of having an experience which can be known, the anxiety intensely captures the person within a whirlpool of dread which becomes an enclosed space without movement, a narrowing of the breath and a cracking of our shells of protection.

Those who follow Lacan might be found talking of anxiety as a “pure presence without absence, the lack of a lack” (Richard Klein). Lacan’s understanding of anxiety turns upside the Freudian formulations of anxiety as a state of anguish produced by the threat of (superego) punishment and instead we find ourselves in the overbearing presence of an object, albeit one that might appear as a kind of necessity to our sense of self. Richard Klein observes that Freud’s second great discovery is that we can enjoy in ways that are not in our best interest, yet deeply enjoyable. We can get stuck on things.

In more contemporary work we can find Medard Boss and Rollo May, who follow Kierkegaard, suggesting that anxiety involves freedom, a going beyond, the unsettling or even a destroying of a present sense of security. These new possibilities, freedoms, gives rise to the tendency to deny the new potentiality, a dizziness when confronted by the revelatory possibilities which take one outside the comfort zone. This dimension of anxiety involves an opening up, the fluidity of uncertainty, flow. The unfolding affect of vibrating life, unknown thoughts, intensities flowing through one’s entire being which open new ways of being alive, engaged, and active.

Despite the variations of theoretical model, what appears regularly is the broad structure of an idea, one in which anxiety is a response to some kind of information or signal. Too much information can result in information overload. The wrong kind of information can result in maladaptation and withering. Anxiety within the contemporary moment can often arise from the signals of endless demands and limited resources. Here it can expose the modes of capture, ways of trying to penetrate our dreams to extract whatever surplus life and labour remains. Capital cries for attention in the information age, fighting a war over our attention that overloads and overwhelms, prompting attempts to escape from the anxiety into self-care or alternative worlds but we can easily find ourselves producing defences that quarantine us into place, producing a kind of psychic lockdown. Both blown minds and closed minds arise from the ongoing class struggle in our heads.

Anxiety can be experienced as a standing still, transfixed to the moment yet fragmenting. Paradoxically, it is a catatonic-like state, yet with thoughts racing faster and faster and faster. With each failed attempt to bring about a sense of calm the speed of thought increases and produces unforeseen associations which jump and break with the conventional linguistic pathways, a process which can allow ideas not held before. This involves a temporary break, even a florid state of engagement with another time and reality that often alienates the person from others, and which often make it impossible for them to get through the day and manage practical tasks. When getting through the day, to feel crippled by anxiety, it is immensely helpful to have self-help strategies, protocols, a tool kit, and external resources to plug into. The danger, however, is that the tool kits support a broken relationship to the world and a broken mechanism of life. The complexities of anxiety are not to be underestimated and simply solved because they point to something beyond the response – the anxiety – and towards the signals and relationships that surround those responses. It might be, for example, that we are right to feel anxious, simply wrong about what we think we are anxious of.

There is something paradoxical about anxiety as there is another way to experience and think about anxiety. Let us take a moment and think of anxiety as the state of being intensely affected as one rides the wave of the new, on the lookout for interesting possibilities, breaking the chains of habit in a process of de-territorialisation that opens onto new futures within a process of becoming multiple, the invitation of difference. Becoming alive and staying alive, to feel life, is not without anxiety. Anxiety is a flow that takes one in different paths to the safe, the familiar. Anxiety can end up as an emotional partner to depression, phobia, terror, and psychic fragmentation. Alternatively, this site of intensity, this affect vibrating through us, can transform and allow for the unfolding of a new relationship to the world. There is the emerging potentiality of this new existence, a unique way of being connected to the earth and life. This possibility is sometimes experienced as an attack on our present security, what RD Laing calls ontological security, the known and familiar, and can lead to a crisis.

Let us return to the image of the different generations and the varying mindsets that arise through the sociogenic processes of culture and history. Auden’s poem, The age of anxiety (AA), is more of a poetic play, closer to what we meet in Shakespeare or Milton, and quite distinct from the short observational expression of a moment that is the more widespread form in which the poetic is met. The four characters of this work act as conceptual personae, each articulating a way of being human and a way of failing. Their anxiety is in the context of “war-time”, a particular form of time. Auden describes a situation of “…war-time, when everybody is reduced to the anxious state of a shady character or a displaced person, when even the most prudent become worshippers of chance” (AA: Part One). Within this space we find his characters meeting, on the lookout for those interesting possibilities. The whole work presupposes this peculiarity of a situation of displacement from the previously habitual everyday moment of depressive stability and describes a scene only available from within a space in which experimental breaks with ‘the way things are’ are to be welcomed, embraced, sought after. The poem opens in a bar, a space lauded by Auden in the opening lines precisely as a kind of special place of open, chance connection within the wider landscape of disconnection produced by war-time.

The characters play, act, and engage in a game without strategies, a conversation. They try to meet life, love, meaning, something ‘grander’ or ‘transcendent’ to the banality of the disaster they live through. Auden’s scenario might remind one of those long drunken discussions in which the world is put to rights or some profound knowledge is felt to be found. Towards the end of the Auden’s narrator again comments, describing the scene as one where “alcohol, lust, fatigue and the longing to be good, had by now induced in them all a euphoric state in which it seemed as if it were only some trifling and easily rectifiable error, improper diet, inadequate schooling, or an outmoded moral code which was keeping mankind from the millennial Earthly Paradise.” (AA: Part Five).

The tenuousness of these moments of insight, their fleeing sounds, and images, make up much of the atmosphere of the scene. Underpinning them, however, is a concept of the human as bound up with the need to ‘play act.’ Towards the end of the poem, in the narrators opening to Part Five, Auden outlines the following ordering of the universe of the human:

“…only animals who are below civilisation and the angels who are beyond it can be sincere. Human beings are, necessarily, actors who cannot become something before they have first pretended to be it; and they can be divided, not into the hypocritical and the sincere, but into the sane who know they are acting and the mad who do not.” (AA, Part Five)

This distinction between those who know they are acting and those who do not may be a poor criterion for marking a divide between sanity and madness, but it does point to an important moment of doubling and haunting. The human is haunted by the human. Or rather, the human adult is haunted by the human. Maturity marks a moment of masking made real, of ‘becoming something they have first pretended to be’.

This ontology of the human, as a doubled creature, plays out in various forms and presents as a kind of tragic situation. Describing the motivation behind the complexity of Auden’s poem, Alan Jacobs refers to “Auden’s conviction … that ‘the great vice of our age … is that we are all not only ‘actors’ but know that we are’. We are ‘reduplicated Hamlets’ in that we are eternally and pathologically self-conscious” (AA, pxxxix). Never less than two and yet never more than one, this human is always uneasy with itself.

Yet here we find this peculiar tension between a recognition, on the one hand of a time of production of subjectivity, of a war-time in Auden’s case, which sits uncomfortably alongside this apparently eternal nature of self-consciousness. Which is it to be? An eternal shape to the human being – a fundamental structure, be it physiological, psychic, or philosophical? Or the time of production of a particular kind of subjectivity, a particular kind of mind-set diagnosed and named in the form of an ‘age’ or ‘generation’?

A productive response to this tension is to draw on Frantz Fanon’s concept of sociogeny. In biological terms there is already a distinction between phylogeny and ontogeny, between the species being and the specific human being, each of us a variation on a theme that has limits but within which an intensity of variation creates huge depths of incarnation. Such phylogenetic and ontogenetic tensions exist across life but within some forms of life biology is entangled and complicated by the social, such that there is a social being and the subjectivities of specific members of the social. This obscure and technical distinction is crucial because it allows us to notice something. If we conceive the human as a result as much of sociogenic factors as of phylogenetic or ontogenetic factors, then we open the possibility of seeing moments in which some phenomena which we might otherwise think were biologically structured might in fact be socially structured. Without such a possibility we find ourselves in the crude world of biological determinist, even eugenic, explanation. Why is schizophrenia statistically more prevalent in one segment of a population more than another? Why is economic wealth found more there than it is here? Is it written in our genes? Fanon’s vehemence in this regard is particularly powerful because it writes itself into concepts of subjectivity, sanity, and colonisation. It opens the potential of a world made up of a plurality of minds, a plurality of subjectivities.

It is with this tension in mind, when it is encountered between processes and the personification of processes, that we found the expression ‘political autism’ appearing in our Breath text. As the social processes shift, so the personifications of that process alter. We propose a set of factors to be foregrounded in any understanding of our contemporary processes that coalesce around the role of the breath, factors that range from the slogan ‘I can’t breathe’ to the crisis of a climate process that can be understood as a shift in the ‘breathing’ pattern of the Earth. The persistence and temporality of both the ecological crisis alongside the crisis of race and colonialism articulate together in that slogan ‘I can’t breathe’. These form a new kind of wartime, one distinct from that in which Auden found himself as it is more dispersed, disavowed and never ending. A new kind of age, a new time of production of subjectivity, one in which the temporality of the crisis flows through us in a peculiar way, on a scale and time span remote from human experience and individual moments.

Within the flow of this crisis, we find ourselves caught in a complex experience, in which the crisis is continuous. Never ending. Deliberate and yet seemingly beyond politics, reason, or choice. It becomes a newly naturalised form of the social and within this new normal we find people overwhelmed, unable to meet the world and responding by withdrawal, muteness, and comforting self-stimulation (Netflix and chill) combined with intermittent expressions of rage and hatred of the other. Protest still occurs, rebellion even, but it seems too often to have nowhere to go and instead of opening a future it burns out its participants until they retreat to a survival pattern of behaviour that we described as ‘political autism’.

Two things need to be said at this point. First, the term ‘political autism’ is highly problematic and unworkable, for specific reasons that are themselves interesting but that we will have to discuss elsewhere. Second, the need to notice, diagnose and try to name the specific time of production of subjectivity (the age) appears as perhaps the most important task facing anyone who might, in any way, think that there is ‘something fundamentally wrong’ in our contemporary social structures and the subjectivities – the humans – that are produced within this age. Whilst we might have got the name wrong, the need for the name remains.

2 Responses

Where’s the listening file?

Hi Helen, the podcast page with the audio is here:

https://staging.freudianspaceship.com/episode1-anxiety/